Kosovo’s Twelve-Day Clock and Belgrade’s Long Shadow

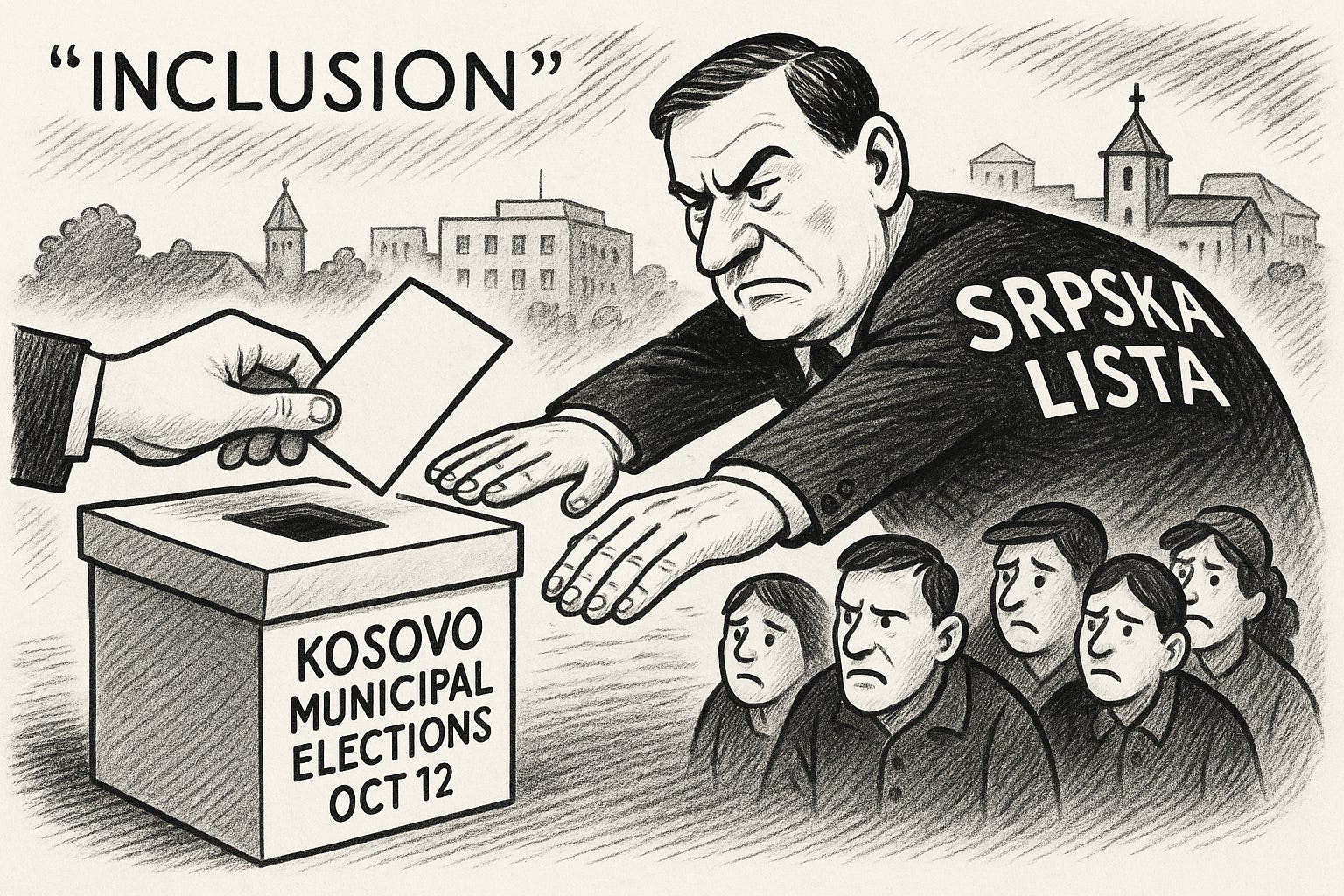

Include Serb voices without surrendering sovereignty: elect representatives independent of Belgrade’s proxies tied to Banjska, strengthen institutions instead of weaponising procedure.

The day after Kosovo’s Constitutional Court ruled that Parliament’s constitutive session “has not concluded,”1 the capital felt suspended between procedure and power. The court’s order was spare and unequivocal: the Assembly that first met on April 15 cannot be deemed constituted until it elects a Deputy Speaker from among the Serb deputies, and lawmakers now have a fixed window: twelve days from the decision’s entry into force to finish the job2. The message was legal, not political. But in Prishtina, where procedure so often masks attempts to pry open the state from within, its political implications were immediate.

Foreign missions lined up with familiar refrains. The OSCE Mission in Kosovo “took note” of the ruling and reaffirmed its “strong and unwavering support” for the Court’s authority3, warning against politicisation of the judiciary and insisting that decisions “must be respected and implemented fully.” The EU’s ambassador in Prishtina, Aivo Orav, urged parties to “constitute the Assembly and form the government” as quickly as possible4, saying Brussels is scrutinising the Court’s decision even as it presses for a return to normal governance.

The lines are boilerplate, but they matter: they telegraph international expectations while skirting the central dilemma, how to meet constitutional requirements without validating a political machine directed from Belgrade.

Inside Kosovo’s political class, reactions revealed the split screens of the moment. “There are only two paths ahead: either the Assembly is constituted or the country goes to elections,” declared Arben Gashi of the LDK5, framing the Court’s instruction as a binary. The Democratic Institute of Kosovo’s Eugen Cakolli, long seen as aligned with the traditional opposition6, called the ruling a restatement of an “already known standard”: no Assembly without a Speaker and all Deputy Speakers, while adding that the right to nominate7 “cannot be a tool of blockade or blackmail.” These are technically accurate readings. They also elide the crux: who gets to stand as the Serb community’s nominee, on what terms, and with which loyalties.

Beyond the statements lies the battlefield of facts. For a decade, Serb List has dominated Serb politics in Kosovo while functioning as Belgrade’s conveyor belt. Its leaders have held posts in Prishtina even as they drew salaries from Serbia’s “parallel institutions” structures Prishtina deems illegal. On September 24, 2023, that dual-track politics crossed the Rubicon8. More than fifty armed men stormed Banjska village, killing Kosovo police sergeant Afrim Bunjaku and sparking a daylong siege around a monastery. Within days, Milan Radoicic, then the Serb List’s vice president and a long-time power broker in the north, admitted he organised the assault. He remains at liberty in Serbia. Interpol notices followed, and Kosovo prosecutors went on to indict9 45 suspects for terrorism and related offences10. Serbia insists Radoicic acted alone; Prishtina says the operation was orchestrated from across the border. Whatever the ultimate judicial apportionment of responsibility, the through-line is not speculative: the political arm that claims to speak for Kosovo’s Serbs has intersected with men, money, and logistics linked to a Kremlin-aligned Serbia’s incursion on Kosovo’s soil.